There have been many negative effects on education that stem from standards and standardized testing. These have been discussed and rehashed over and over through the years since standards and testing began. I have been looking specifically into the direct effects on math instruction.

One of the biggest negative effects of standards based education is the narrowing of the scope of what our children are learning. Due to the very specific way that the standards are written and tested, most districts and curricula have narrowed their focus to the specific skills that are listed in the standards. I live and teach in the state of Virginia and I will be using specific examples from the VA SOL’s, but my research shows that Common Core states have similar issues and I am guessing that other states with their own standards would prove the same.

When I started interviewing students in grades 3-5 who were struggling with math, I noticed some big similarities among them. The most noticeable is that they struggled to count numbers higher than 100. When I started looking into this, I realized that in Virginia, there are no specific standards for counting past 120 in second grade. Because of this, most teachers don’t do any counting work past that goal.

The counting standards in Virginia include counting forward and backwards to and from 120 and skip counting by 10, 5, and 2 from any multiple of that number up to 120. Almost all of our students are successful with these skills, so we didn’t really think past them. I will admit that when I was a third grade teacher I was just as guilty.

It used to confuse me why, if my students know place value, how can they struggle so much with things like rounding, comparing, and ordering??? What I have discovered is that students struggle with these skills because they can’t count the numbers they are expected to work with. In VA we expect 3rd grade students to work with whole numbers up to 6 digits and 9 digits for grades 4 and 5, but there are no specific standards that require counting those numbers.

My belief is that if any numbers we expect students to work with, we should also make sure they can count them. We should be able to pick a random number and students should be able to count forwards and backwards from that number by 1’s, 10’s, 100’s etc… Counting directly relates to the skills of comparing, ordering, rounding and mental computation. If our students were comfortable with counting these numbers, then teachers wouldn’t have to rely on shortcuts, poems, procedures and tricks to teach these skills.

When I was in school, I can vividly remember counting chorally well into middle school. Choral counting and counting circles are a great way to bring counting back into classrooms. Choral Counting and Number Talks are the 2 routines that have had the biggest positive impact with the struggling students I work with.

First of all, here is a link to a book that will help you start Choral Counting in your own classroom. It is called “Choral Counting & Counting Collections” by Megan L. Franke, Elham Kazemi, and Angela Chan Turrou. If you don’t have the means to get the book, just google choral counting and you will find a wealth of information and videos that you can use.

Here is a great video that shows choral counting in an upper elementary classroom. https://vimeo.com/44837082

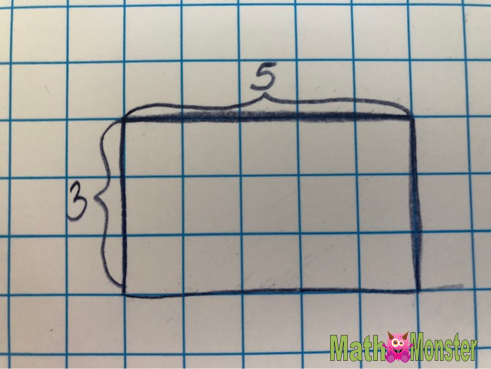

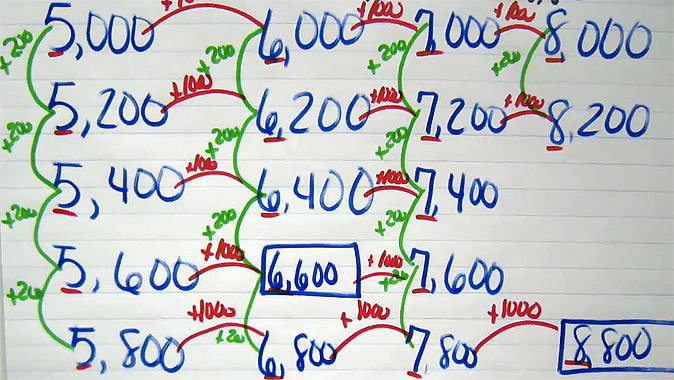

Remember, if you are starting from scratch, use easy numbers to help students learn the basics of choral counting. I usually start with 3 digit numbers and skip count by 5’s, 10’s, or 100’s. Eventually you want to be able to start at any number and skip count by a variety of numbers that cover the numbers that your class is responsible working with. (In VA, that would be whole numbers up to 6 digits in third grade and 9 digits in fourth and fifth grades.) The most powerful part of the activity is looking back and finding the patterns and discussing what they notice and wonder about.

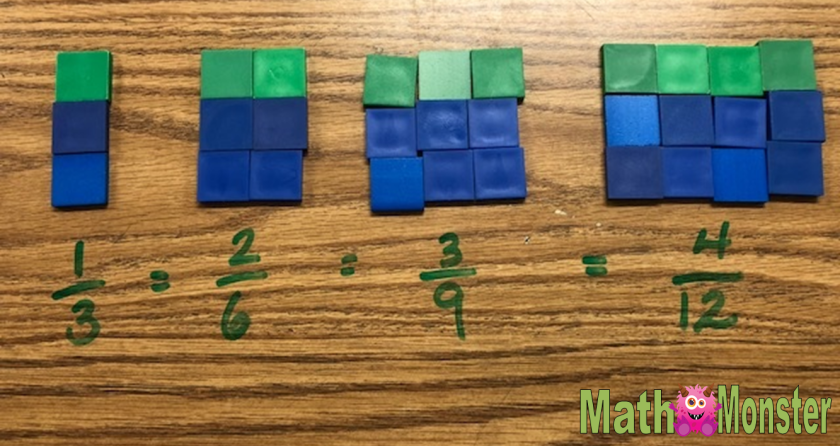

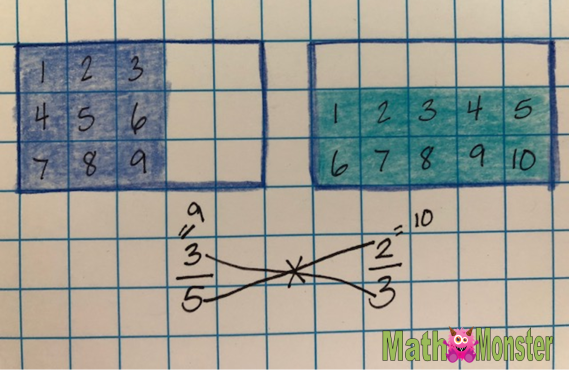

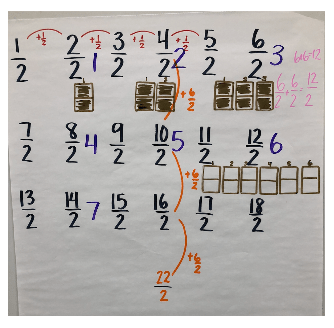

Don’t forget that you can also do coral counting for fractions and decimals. Here is a video for a fraction example. https://www.engageny.org/resource/nti-november-2012-rigor-breakdown-skip-counting-by-fractions

And here is a wonderful decimal example. Listen to the students discuss the patterns. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qf_VBRFCnuc

Counting Circles are another great routine that takes no preplanning. Anytime you have a couple minutes to kill you give the kids a number and the amount you are counting by and go “around the circle” counting. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yk0_sa-wo_U

Remember that the more fluency students have with counting numbers the more those numbers will make sense to them.