This is part 2 of our “Down with Math Rules!” series. In this post I will focus on the subtraction poem. I’m sure you’ve heard it. It goes something like this:

More on top?

No need to stop!

More on the floor?

Go next door…

And get 10 more!

Numbers the same?

Zero’s the game!

This poem is supposed to help students remember when to regroup when doing multi-digit subtraction. I’m not implying that the poem is incorrect or that it won’t assist students, my problem is that most teachers start with the poem and only teach the traditional standard algorithm.

Students should be comfortable with counting to 100, counting using hundreds charts and number lines, basic addition and subtraction facts and be able to compose and decompose numbers through 20, especially the number 10. If students have had regular exposure to rekenreks, number bonds, hundreds charts, and ten frames, they should be comfortable with these skills and be ready to explore multi-digit subtraction. Students who are still struggling with these concepts should receive intervention before moving on.

I like to start my second grade student exploration of multi-digit subtraction with hundreds charts and rekenrek 100’s. Students should have gotten practice counting by 10’s and 1’s on both of these manipulatives while exploring multi-digit addition. After exploring a variety of 2 digit subtraction problems on cards students should have noticed that sometimes they have to go back up to the previous row when counting back the ones and sometimes they don’t.

During the next day of exploration, students use the same cards and look at them again. As they go, have them sort them into two piles: the ones that require you to go up to the previous row when counting back the ones and in the other pile the ones that don’t. Write some from each category on the board and see if they students can discuss what they problems in each category have in common. I will be honest with you that this sometimes takes more than 1 lesson for students to figure out what you want them to figure out. Don’t rush it!! Let them make the discovery, it is much more powerful than if you tell them.

Once they make the generalization, talk about why when the first number’s ones places is bigger than the second number’s ones place you don’t jump up to the previous line. Have students talk about it with a partner and share their thoughts. Then do the same discussion about the other category. We don’t ever teach the traditional algorithm in second grade, so this generalization is just a concept for them to think about as they subtract. Will they need to jump lines on this problem or not?

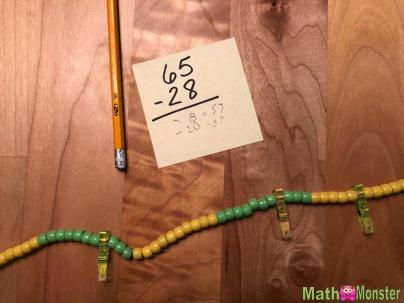

I then follow up with practice on subtracting on paper and beaded number lines and with manipulatives, such as, unifix cubes or base-10 blocks. I encourage students to use multiple strategies to double check their answers. I allow them to use these manipulatives throughout the entire unit on 2 digit addition and subtraction and even on the assessment. Part of their assessment is a math interview, during which they may use any strategy to solve 2 different subtraction problems (one that would require regrouping and one that wouldn’t) and a discussion on why looking at the ones places is helpful when subtracting.

Students will eventually be exposed to the traditional algorithm is future grades, but their conceptual understanding of subtraction and what regrouping means will be essential for their learning of why we regroup. It is so much more useful than a poem that most of them will forget over the summer.