In Part 1 of Fact Fluency, I talked about the fact that math facts should not be “kill and drill” until they are memorized. I wrote that fact fluency has 3 parts: accuracy, efficiency, and flexibility. We should be encouraging students to use strategies that will help them quickly get to the answers. In this post we will look at the strategies for addition facts to 20.

In Part 1 of Fact Fluency, I talked about the fact that math facts should not be “kill and drill” until they are memorized. I wrote that fact fluency has 3 parts: accuracy, efficiency, and flexibility. We should be encouraging students to use strategies that will help them quickly get to the answers. In this post we will look at the strategies for addition facts to 20.

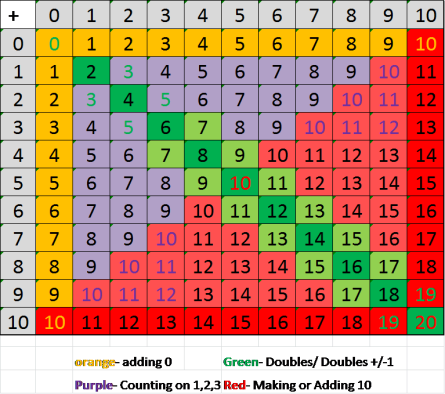

After doing a lot of research and reading lots of information about addition facts, I created my own addition chart based off several I studied in different books and websites. I believe that there are 4 basic types of facts: Zero, Counting on, Doubles, and adding 10.

The first type of fact is “adding zero.” Students should be able to see 0+6 or 6+0 and automatically know that the answer is 6. This is the identity property of addition and students should be comfortable with it.

The second type is “counting on.” This is the strategy that most students without fact fluency fall back on for all their facts. I encourage my students to only use this strategy for 1’s, 2’s, and 3’s. If you try numbers bigger than that, you lose efficiency. Again, students should be able to use the commutative property to know that 9+2 and 2+9 are the same fact and that they can use the same strategy to get the answer.

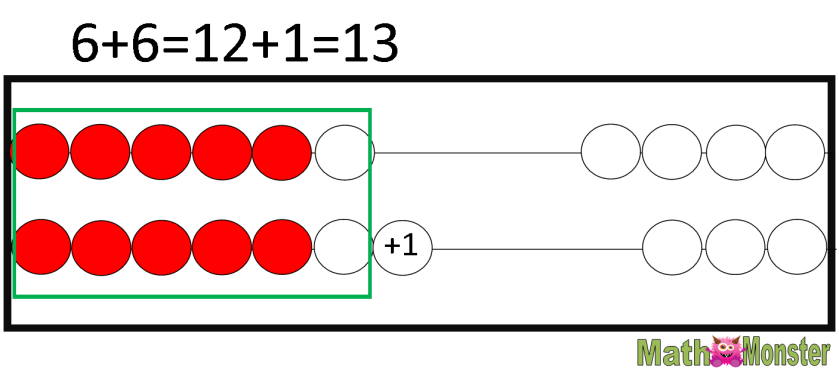

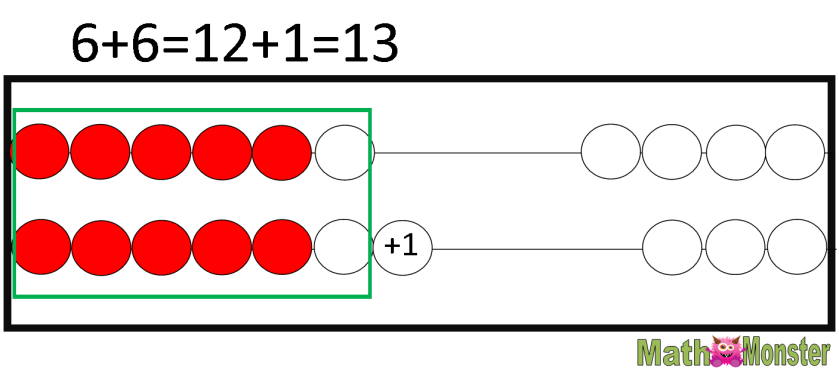

The third type of fact is Doubles. Many students learn their doubles quickly, but many times we fail to use this as a stepping stone to those Doubles =/- 1 facts. If they know that 6+6 =12, they should be able to quickly figure that 6+7=13 because 7 is one more than 6 and 13 is one more than 12. If you have been using the number rack (or rekenrek) and 10 frames, this is easy for student to visualize.

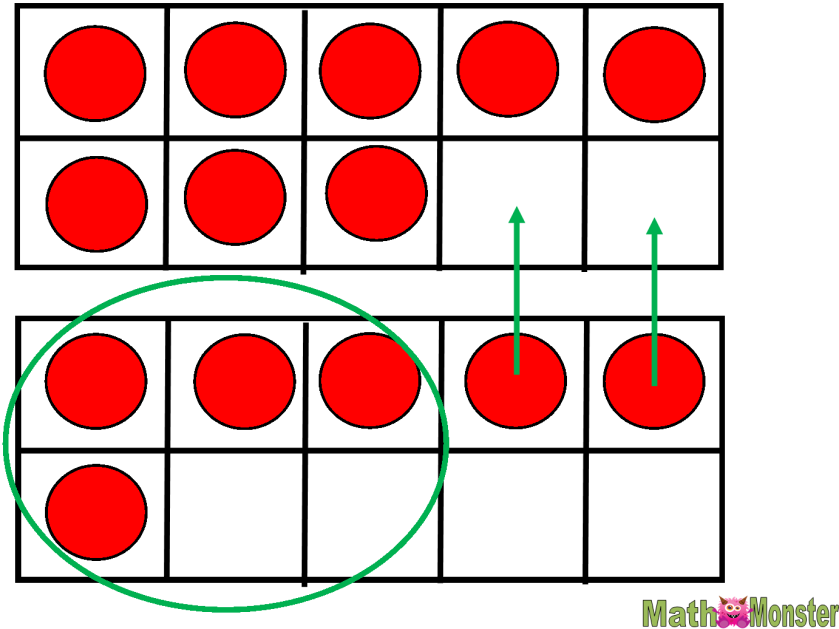

The fourth type if fact is making and adding 10’s. Most students are quick to learn their 10+ facts. Again, if students are familiar with 10 frames and math racks, this strategy will be easy for them to visualize. If they are comfortable with making 10 in all its combinations, they should be able to easily break apart numbers to make 10 and add to 10. For example, 8+6=, students know that 8 and 2 are 10. They break 2 off the six to make the 8 into a 10, leaving 4 behind. They already know that 10+4 =14.

If students can become comfortable with these strategies they will be able to develop fact fluency. This will also help them with subtraction as you talk about fact families and use addition facts to learn subtraction facts. Eventually, as students become more and more fluent, many of the facts will be memorized without the “kill and drill” nightmare.

Part 3 of Fact fluency will focus on Multiplication and division facts.